Forms of Engagement: In Conversation with Marcelo López-Dinardi

MAKING THE PUBLIC–COMMONS. Image Courtesy Marcelo López-Dinardi

Pouya Khadem (PK): I think both of us were quite impacted by Silvia Federici’s talk1 last night, so I want to start from there. She calls architects to engage with, and care for, issues around systematic suppression of minorities and more vulnerable people distanced from power. How can architecture afford this while the process of constructing a building is prominently tied to wealth, and higher budgets provide more freedom to architects? Shall we perform as a Trojan horse, using the wealth of our clients to critique the system that produces the clients? Or perhaps we don’t need architecture anymore and instead of assembling, we should disassemble, like the legacy of Gordon Matta-Clark suggests that you have written about.

Marcelo López-Dinardi (MLD): Well, on the one hand, the assumption that we first need to challenge is that of considering buildings as structures of power, or structures that are associated with the reproduction of power. Not because they have not been, but because there’re plenty of examples of fantastic buildings, and I’m thinking about housing or public architecture and infrastructure, that are not that. We need architecture now more than ever. For instance, architecture built for poorer communities or in developing countries is treated as an inferior version of architecture due to a lack of wealth put into it, despite any significant architectural qualities it may have such as a careful attention to site or resources management. We should challenge the assumption that buildings are inherently products of high power in the form of wealth. Yet, we, architecture, still need to reckon—widely, with the role architecture had as modern instrument in building a colonial world that deliberately destroyed indigenous cultures and enslaved others in the “geographical and cultural uprooting of entire populations,” as Achille Mbembe explains in Nechropolitics.

On the other hand, we should distinguish between the practice and the product of architecture. The practice of architecture is not solely about producing buildings; it is about drawing, conceptualizing, listening, and understanding social and ecological needs—it is to work with these and produce a response. We should think about how we do what we do, about protocols, policies, and logistics, about how we spend our time and how we run an office, about what tools we are using, and how they impact our thinking. The reconsideration or reformulation of these ideas needs to happen much earlier in academia, where we easily reproduce both positive and negative aspects of traditional practices. We need to begin treating education and the studio space as an alternative to reproducing the colonial legacies of our discipline and profession.

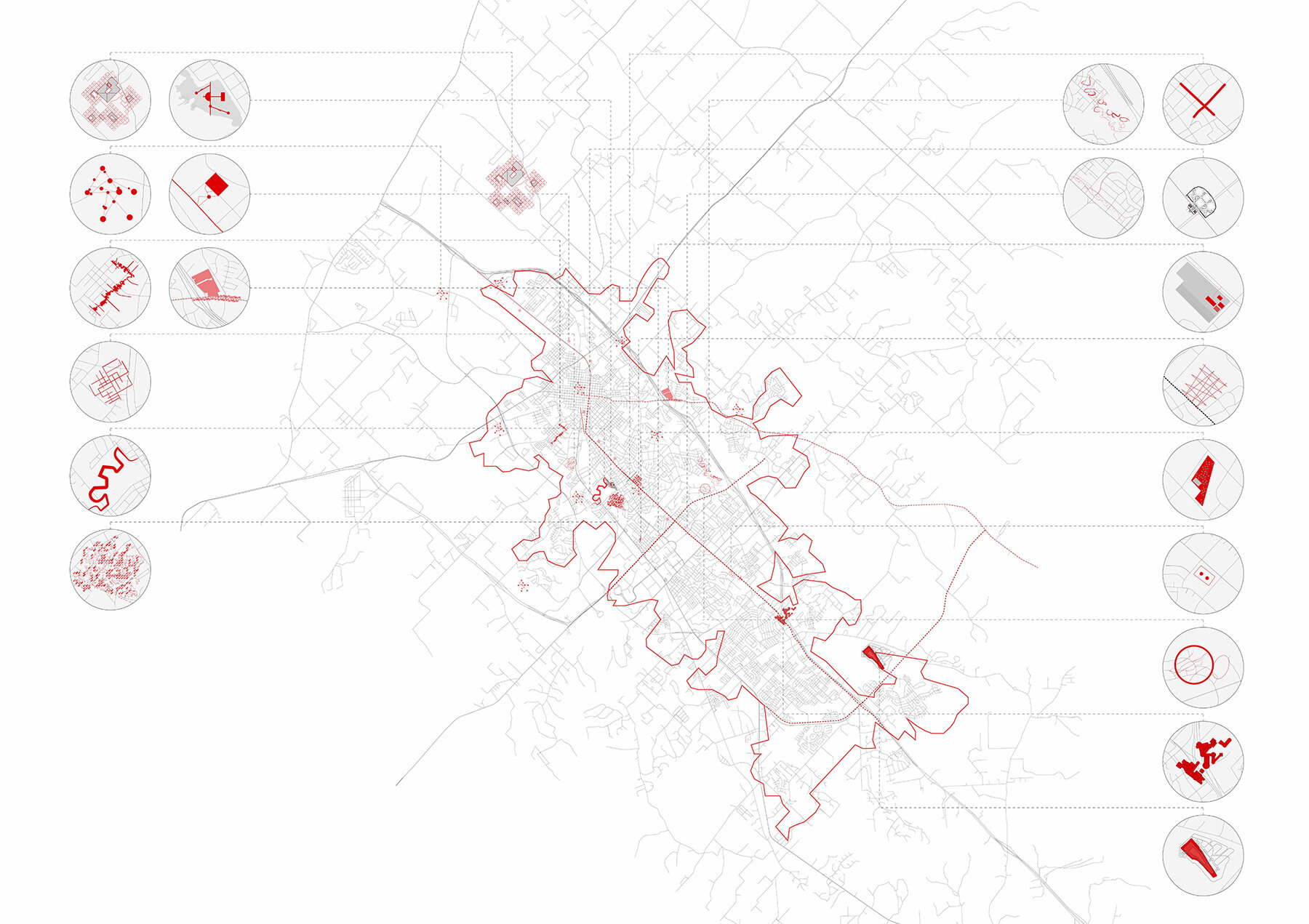

Anxiety and desperation—for finding a job and entering the pyramid of power that is the architecture market—are the sources of depression for every architecture student in their last semester. This is extremely counterproductive to the practice itself because there is so much collective knowledge and power that we could have if we treated this system of distribution differently. Why are architectural practices not fully multidisciplinary and horizontally led? Groups working together thinking about practice through the lens of cooperation, not competition. This can be started and extended from academia, making architecture more inclusive of both the people who are practicing architecture (marginalized races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic groups) and of the products of architecture as expanded practice. We need assemblies, public infrastructure assemblies, commons assemblies. These are the topics of my studios at A&M since I arrived in 2018, from which I just produced An Agenda for Bryan-College Station.

This drawing documents the twenty projects selected to articulate the Agenda for Bryan-College Station. Image Courtesy Marcelo López-Dinardi

We need to assemble, still, but more around the ways Matta-Clark did in Pig Roast (1972) under the Brooklyn Bridge in New York. That’s not the usual work you hear cited about the artist in the architecture circles, he had multiple other things to offer beyond building cuts.

PK: We are talking about a reformation in which academia becomes the generator of practice. The question of academia/practice also appeared in the 1960s and ’70s when the embedded elitism in academia was heavily criticized. The context of that era is not that much different from ours today in 2021: both are replete with ambitions of cultural reformation. To loosely compare our time with the 1960s, do you think another phase of retreat from the elitism of academia is likely to happen?

MLD: We need to be careful with conflating elitism and academia in a single stroke. I belong to the group that thinks that we owe a lot to the 1960s and 1970s, in terms of how they offered lessons for issues we still need to be looking at. In particular, the revolts in May 1968 with architecture students from the Pedagogical Unit 6 taking over the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, were an act of refusing to be educated under principles that they understood didn't belong to their time, but also didn't belong to their concerns. Similarly happened in Morningside Heights and Columbia University but really everywhere (the West Coast, Mexico, etc.). This was beyond elitism, it was a straight action against architecture’s own Western-extractive ideology, and to the so-called canon. And it was a reaction of understanding, perhaps, that the role of the academic institutions was too much connected to an “elite” idea of the work of the architect. So, the academy is not in any way exempt from replicating these same maladies, but also not a lost ground.

But back to today. We already knew all of this—these pitfalls, to put it lightly, could provide the opportunity to redo practice, perhaps even redo the profession, or at least the pedagogy where we have more direct engagement. Where things get more complicated is that the debate, in the US particularly, evolved in such a way that certain architecture schools got paired with an attitude of anti-intellectualism that was the product of the deregulation of knowledge and the privatization of education beyond architecture. Others continued standing on their privilege.

Nearly every thought related to the humanities in the 1960s is associated with the left, with socialism, and with practices that were much more critical of the issues of their time, and of capital evidently. The operation of reproducing the schemes of power that were being developed in the privatization of every sphere of life (from housing to health and education) was passed onto the academy, making it difficult to continue some of the battles from the late 1960s and early 1970s. The academy was being commodified and contained within that larger, interiorized world of the neoliberal dominion.

If we trace a critical history of (and we must), for example, the figure of Peter Eisenman and the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS) in New York City, what was cultivated in those twelve-to-fourteen years on the East Coast was precisely the construction of an elitist notion of architecture, one associated with the Museum of Modern Art, Philip Johnson, and so forth. They were aware, as it is written in documents in the IAUS archive collection at the Canadian Centre for Architecture. What we see there is that those who had the power perhaps of creating an alternative academic space following the predicament of the 1960s, of rebellion, refusal, and experimentation, realized it within the most conservative political—and architectural positions. But they also reproduced, and even set up, the same distinctions happening in the US political arena, from centrist to center-right—and absorbed whatever remained from the left. Architecturally speaking, if I could say that the left in architecture was abandoned, at least discredited and diminished (not to suggest it was exempt of criticism).

If I can continue with New York for a moment, the city had the evidence of all the issues we still face today. The IAUS decided to take the conservative route. That’s a bit of what I have worked on “Audience and Discourse: Cross-Atlantic Exchanges in the Context of the IAUS in New York City, or Inventing New Eurocentric Architecture Institutions in the 1970s.” If we think about the figures that arrived then who were more critical in their beginnings, like Bernard Tschumi or Rem Koolhaas, they eventually relaxed their political positions. There's a text called “The Environmental Trigger” where Tschumi put into words his position. Thankfully we have, for example, the work of Nandini Bagchee in her book Counter Institution: Activist Estates of the Lower East Side that shows us engaged alternative efforts to that of the mainstream architectural worldview in the same period. Or the biographic work of Sharon Egretta Sutton experience at the time in When Ivory Towers Were Black.

Let’s go back to reformation, academia, and practice. From the surge of corporate America in the Post-war onwards the production of architecture, including the still modernists of the 1970s, the neo-traditionalists of the 1980s, the wave surfers of the 1990s, and the fully depoliticized post 9/11 practices, their positions—their political positions—are overwhelmingly center and center-right. Architecture like everything else was devoured by the “stealth revolution” of the neoliberal apparatus.

Architecture pales in the face of this call to arms, urging us to abandon the idea that we can make changes. At least changes outside the veil of an extractive culture and a neoliberal imagination. This mentality exists across the board in academia and practice, with scarce exceptions. One key evidence for this is in the countering of having critical positions even in acknowledgment of limits and contradictions. Being critical is faced with demanding questions, protectionism, and acceptance of fate —but what is the answer? What are you proposing? What is your solution?

In the alienation of the figure of the architect, we break ties with empathetic networks. Architecture schools are not a place where we learn how to create caring ties with the world. This attitude begins with the studio from day one; in the first semester (foundational) studio, every undergraduate student is asked to remove the complexity of reality to work on elements like surfaces, lines, and volumes. Capped later in the technocratic integrated or comprehensive studio. The Western worldview of geometry instrumentalized as spatial and formal occupation, plus authorship, set the entry point to architectural thinking. It is a radical break from everyone’s life, we treat students like empty vessels, they are not. For us to reconsider this, we need to do our part beginning in the studio space.

For example, I cannot change everything I aspire to. But I can work in my studio space. It is a very real space. The more that we acknowledge the time we spend together in the studio, or in a classroom or a seminar—the more that we treat it as real time, real space—we will begin, perhaps, to recognize the kind of consciousness that Silvia Federici was asking us to have. To care for the people who are sitting with you at the table, to understand their backgrounds and vulnerabilities or talents, and to have proper relationships with those in the studio setting. Then we could start thinking about how we live together.

I'm less concerned about architecture as a product, meaningful, rich, stimulating examples abound. We know so much about how buildings behave, and what are better and worse buildings in terms of energy, materials, etc. We know less of labor relations, landscape, ecology. I think architecture is a practice that could also be made with a different format, in which the participants—and us as participants of the making-of of the practice—account for a variety of forces, questions, and needs. This calls us to reconfigure the ties, the links, and the networks in which we participate.

I will bring the word engagement to wrap up this question: one of the ways that I approach teaching and practicing architecture is by exploring forms of engagement. I’m proposing to understand the architectural project, design, as a form of engagement with real questions, a topic, a group, an environment, a culture, a location. In this effort, I aim to expand the scope of practice. We treat the word engagement as if it is only a question of being good with your local community. This is one aspect of engagement. Receiving donations from sources that maybe we shouldn’t or relating to given power structures for the same reasons—these are also forms of engagement. I'm ambivalent in the “Trojan horse.” More than ever, we need to be direct, expose ourselves, and embrace the faces of difference in the territories we share and occupy all institutions and places.

The institution is an apparatus, and we need to acknowledge that we also make the institution every day as individuals. The State is an apparatus. We operate as citizens, right? Well, not everyone, yet we are subjected to the State as such. In 200 Hours, for example, a project part of a larger research on debt and the colonial legacies between the U.S. and Puerto Rico (where I did my B.Arch.), I show how the no more than 200 hours of U.S. presidents official and unofficial visits to Puerto Rico in the more than 120 years of occupation of the Caribbean archipelago, produced the largest debt of all. Puerto Ricans were assigned U.S. citizenship in 1917 but cannot vote for president in their territory unless they live on the continental U.S. If we don’t consider these facts as individuals there’s no undoing of the colonial subject and the possibility of institutional reformation.

200 Hours Map. Image Courtesy Marcelo López-Dinardi

We are individuals and institutionalized bodies. As we acknowledge our own political self beyond the institutionalized body—imagining us liberated, practicing a practice of care, commonality, and cooperation—perhaps we will open up avenues for more inclusive forms of work not based on extraction or the legacies of imperialism (including elitism).

Jimmy Bullis (JB): As architects traditionally tasked with making space, enclosing space, and defining space in these active and authorial modes, it feels today as though we are using more terms like reconstituting, rehabilitating, and remediating to describe the work we do. Do we have a responsibility towards undoing something that has been done—as you have explored with Destructive Knowledge: Strategies for Learning to Un-do, or is there some other way to approach these efforts that is less aggressive than that? Or is being aggressive in this regard a good thing?

MLD: I fully embrace the undoing in my work: in my practice, in my thinking, and in pedagogy more than anything. First, because I was very well trained as a modernist architect, meaning I was trained to design in a way that I am in control all around. I am trained to have control over the things that I am working with and to actively suppress the things that I cannot control. That has required, in my last decade of work from almost twenty years, to fully jump into the undoing of my own way of thinking about architecture. I cannot simply teach a studio based on my own architectural training, it would be antithetical to what I think and do now. This is a challenge and a struggle because it’s always there. I have embraced a kind of personal approach to being explicit, often too much, in explaining and contextualizing what or how I’m teaching. I spend a good amount of time in my classes explaining the framework, explaining why we are doing a project one way and not another. There is a lot of framing ideas, and I think this appeals in part to the principle of undoing.

The other side of the undoing for me, and the reason I believe is relevant, is because there are so many assumptions of what we encounter when we come together in the university as students, faculty, and the institutional community in general. The reconsideration of those assumptions is part of the undoing as well. The space for these alternative forms of work and practice needs to be created, to be carved out. My interest in understanding the work of Gordon Matta-Clark, which came late in my career, speaks to this idea. What I ended up investigating about his work was precisely his own undoing as someone who was trained in the modernist tradition of architecture at Cornell. I am much more interested in the personal motivation of the work rather than its product. He also was invested in engaging, in the process beyond the artworks, sometimes produced as by-product of his actual spending of time. That is why I have been engaging with this notion of undoing, mostly as a way of carving space for alternative practices to emerge. There’s much more to undoing and unlearning, we should come back to this.

PK: This idea of undoing seems connected to the idea of unknowing, and of not presuming to know. Do you think unknowing is as important as undoing? How do you leave room for doubt and uncertainty in your work?

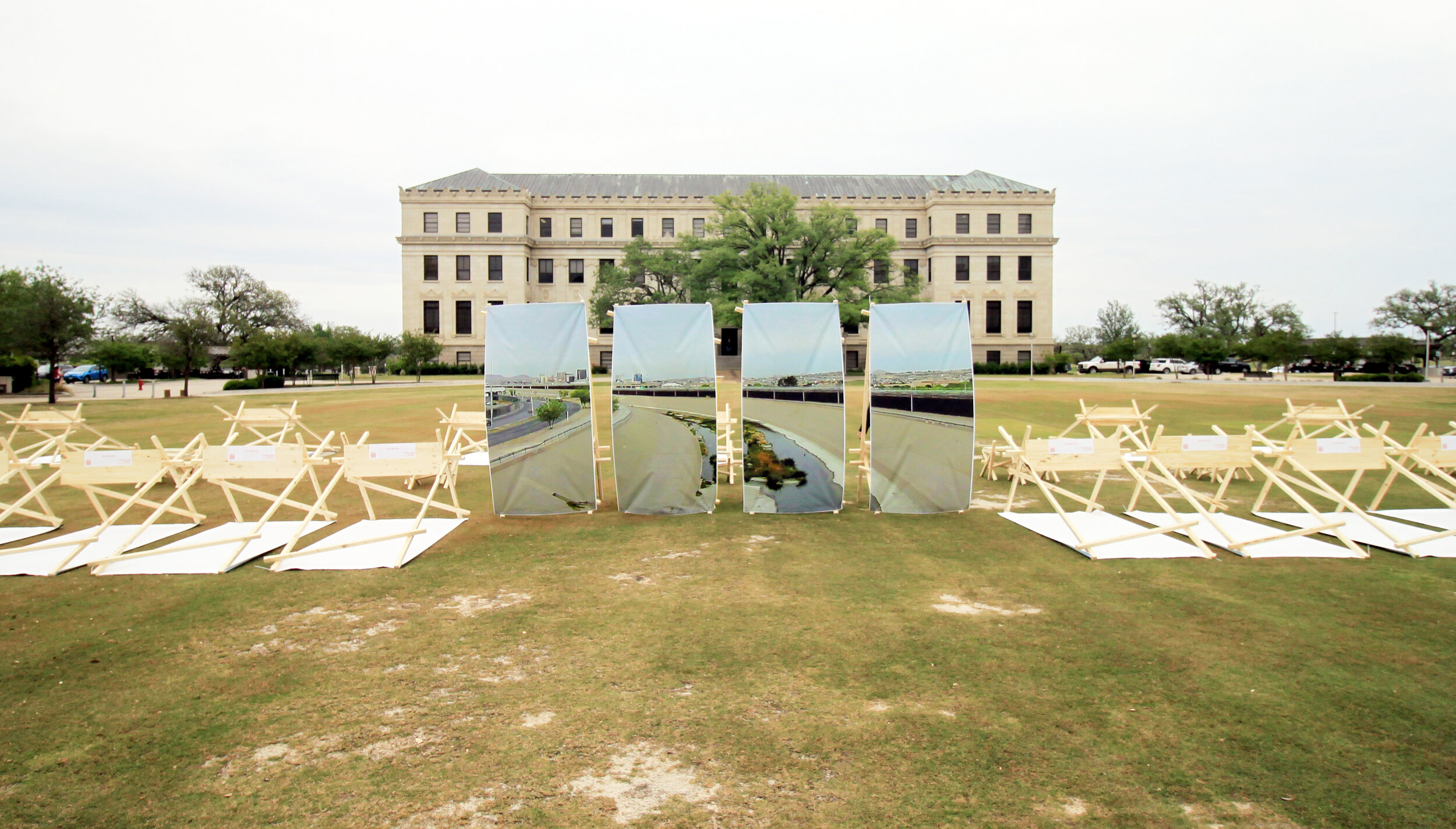

MLD: Unknowing requires precise questions, which is difficult in a complacent, transactional, and attention-seeking world. We are asked to provide solutions to things, not to produce doubt. But we must seek unknowing as a form of practice. And so, I carve a lot of space in trying to craft specific questions, and in extending the time spent developing the engagement with them. I recently did a multifaceted project titled MAKING THE PUBLIC–COMMONS, it included a 10-hour conversations marathon (truly non-stop), and an installation at Texas A&M campus. The conversations marathon with guests from all over the world speaks to this search for unknowing, for common knowledge over expertise. The format exposed me—I evidently do not master all ten topics discussed, even made me vulnerable, as it didn’t allow for much control. The whole project was about asking questions. The installation “brings” the Rio Grande closer to campus in an invitation to ask ourselves our role as academic community in what unfolds there daily. But it is difficult. We still need to learn, and teach, direct forms of engagement that can enact change. This project is one such form.

In teaching, I sometimes spend more than half a semester researching the questions, considering the forms of engagement, before we ever get to a discussion about the “design response.” Not all questions have a design response, yet we still need to craft them and think with them. There is a positive uncertainty embedded in my studio setting that we cultivate by promoting care, listening, discovery, risk, and invention. Grounded forms of engagement and imagination. We need to be more radical by caring, as suggested last night by Federici.

Let me share one more reference to conclude, your question of unknowing is crucial. Not because I say so, but because it is critical too for the project of Unlearning Imperialism, as proposed by professor Ariella Aïsha Azoulay. It is crucial to question the imperial foundations of knowledge, and how it has been used to dominate territories and peoples. We had, and still have, a role in that process of domination. We must work to undo that, and we must work on architecture’s forms of engagement that imagine worlds that seem impossible. We must embrace the future and the horizon of possibility. After all, architecture is all potential.

Marcelo López-Dinardi is an immigrant, architect, and educator based in Texas, and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Architecture at Texas A&M University. He was a founding Partner of A(n) Office (2013-2020). He’s interested in the multiple scales of design; biopolitics and agency in design and education; and architecture as expanded media (publications and curatorial practices). His work as partner of A(n) Office was exhibited in the Venice Biennale of Architecture in 2016 and has written for Avery Review, The Architect’s Newspaper, Domus, Planning Perspectives, Art Forum (China), and lectured at The Cooper Union, Princeton University, RISD, GSAPP, among others. He holds a B.Arch. from the Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico, and a MS in Critical, Curatorial and Conceptual Practices for Architecture from the (GSAPP) Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation of Columbia University

1 Referring to Silvia Federici’s closing keynote lecture at the virtual symposium “CARE-WORK: Space, Bodies, and the Politics of Care,” March 3, 2021, as part of Rice Architecture’s spring 2021 lecture series New Proximities.