Aesthetics of Prosthetics

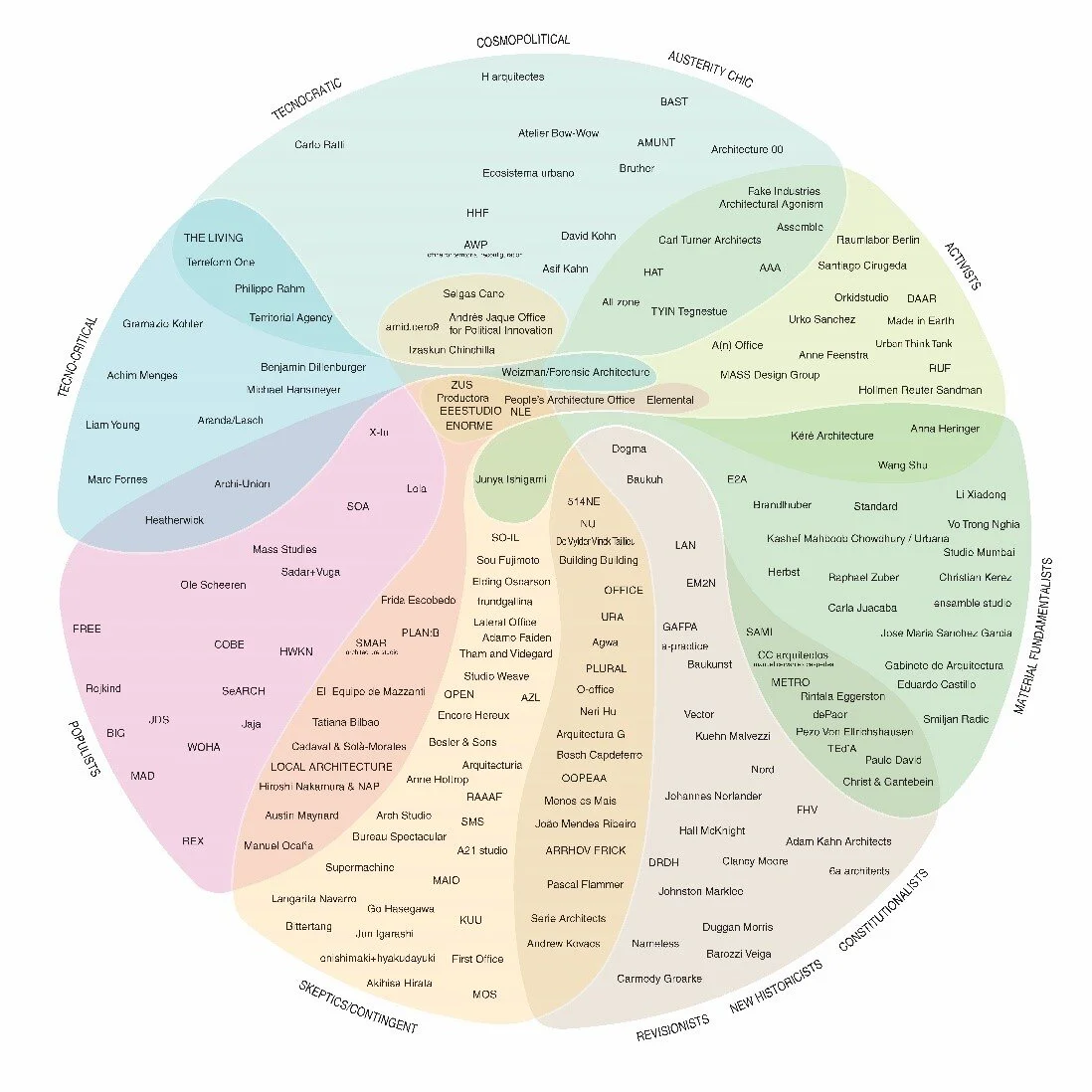

Perhaps one of the most interesting pieces of recent architectural analysis has been Alejandro Zaera Polo’s 2016 diagram (fig. 1): a matrix for reading contemporary design attitudes, or a section in time, as he calls it. The Political Compass of Architecture in 2016 is rich in groups of practices, and Zaera Polo distinguishes eleven categories and defines each of them in his 2016 article published in El Croquis. The crucial aspect of the diagram is that the architects represented in it are relatively young.

Figure 1 The Political Compass of Architecture in 2016

Here, I am particularly interested in Zaera Polo’s “Techno-criticality” category. My reasons for thinking that the “techno criticals” represent what’s most exciting in architecture today are identical to his:

But even if these speculative practices [techno-critical ones] have not yet reached a position where they may become capable of effecting radical transformations of the real, […] I cannot dissimulate my excitement about the critical use of these technologies and those sensibilities, which I believe to contain a much bigger transformational potential than the contemporary retreat into the inner landscape of the discipline— returning to architectural language games and the like, or to the old anarcho-syndicalist rhetoric.i

However complex technology becomes, its relationship to architecture and the way architects use it operates mainly through a mode based on simplicity. By simplicity, I mean a synthesizing approach rather than an expansive one. In other words, architects do not operate within a scientific research method of expansion (as technology does) but relate and work with the technology at their disposal. Technocratic architects will refute this, but it will be argued that architects use technology solely as a prosthetic device, an extension rather than a modus operandi or method. This boundary has recently become incredibly hard to discern, mostly because of what one might call intelligent prostheses, augmenting our brains with digital flows and environments. The ensuing examples illustrate that it is with that simplicity, or distanciation, that architecture gains disciplinary efficacy in responding to technology.

Why, then, is a focus on technology at all relevant today? Shouldn’t we dismiss it altogether and focus on something else? What are the transformative potentials that Zaera Polo is referring to? Slavoj Žižek’s recent book, Like A Thief in Broad Daylight, Power in the Era of Post-human Capitalism, can help provide an answer to why it is important to address technology in our contemporary moment. Žižek proposes to read the ecological breakdown we are undergoing, and the rapidly accelerating digitization of all aspects of our lives, as two aspects of the same phenomenon that can broadly be defined as post-humanity, a term that has recently been enjoying a comeback in many contexts.ii

It happens from time to time that a similar idea appears in two different fields of theory that do not intercommunicate at all – say, in ‘postmodern’ speculation and in empirical science […] Lately, cognitive sciences have proposed their own version of anti-humanism: with the digitalization of our lives and the prospect of a direct link between our brain and digital machinery, we are entering a new posthuman era in which our basic self-understanding as free and responsible human agents will be affected, In this way, posthumanism is no longer an eccentric theoretical proposal but a matter concerning our daily lives. Can these two aspects be brought together into a unique theoretical perspective, or are they condemned to speak different languages? The first thing to note here is how the rise of posthuman agents and the Anthropocene epoch are two aspects of the same phenomenon: at exactly the time when humanity becomes the main geological factor threatening the entire balance of the life of Earth, it begins to lose its basic features and transforms itself into posthumanity.iii

Prosthetics and Architecture

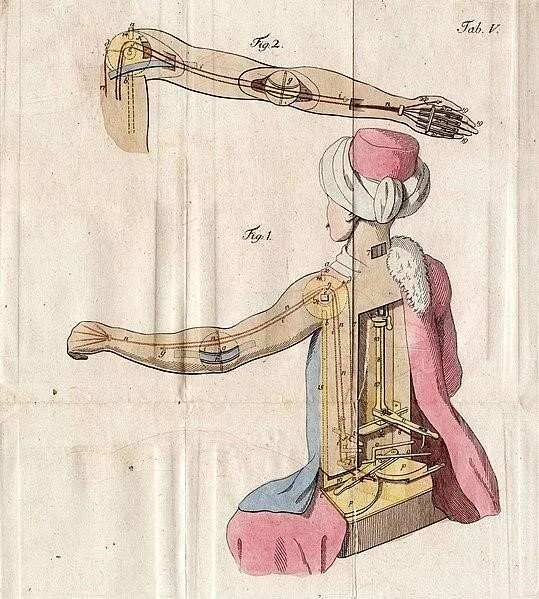

Post-humanity, as described by Žižek, is the cyborg-becoming of humans. This is not a new subject; the idea of machine-enhanced-humans has been around for centuries (think of the mechanical Turk or other similar inventions) (fig. 2) and reached a theoretical peak through cybernetics or Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto (1985.) My intuition about why a focus on prosthetics might be fertile for architectural work to come is the “prospect of a direct link between our brain and digital machinery,”iv as Žižek puts it. This is not theoretical science; today, scientists can control a mouse’s movements and behavior by implanting a chip in its brain.v The catastrophically dystopian vision these brain/computer interface technologies point to does not change the fact that sooner, rather than later, they will become part of our daily lives.

Figure 2 Diagram explaining the illusion behind the Kempelen chess playing automaton (known as the Turk.)

This prospect seems to render any discussion about the digital, parametric or post-digital nature of contemporary architecture futile. As machines become part of our bodies, and our bodies become part of machines, trying to pursue a theory around the technologically complex becoming of architecture appears as timely as questioning the place our liver plays while doing architecture (if you are a heavy drinker, your liver does indeed play a role in your design process, but I digress.)

The Memex and Plato’s Prosthetics

In a recent quirky book called New Dark Age, artist James Bridle digs up the history of some of the technological devices that are now completely embedded in our daily lives. He notably quotes the engineer and inventor Vannevar Bush who wrote about prosthetic intelligence as early as 1945. For Bush, prosthetic intelligence is a solution to both the excesses of specialized research pursued in sciences and to the possible destructive ends of scientific research implied with the invention of the atomic bomb. Bush’s solution is a device he calls the memex (fig.3):

A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.vi

Figure 3: Simplified diagram of Bush's memex.

Further back in time, in Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates presents to Phaedrus what he believed to be a great invention that all should use: reading and writing. But Pheadrus reasons against Socrates by arguing that it is perhaps not a good idea to teach men and women how to read and write, because they might use it to replace their memory.

And so it is that you by reason of your tender regard for the writing that is your offspring have declared the very opposite of its true effect. If men learn this, it will implant forgetfulness in their souls. They will cease to exercise memory because they rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves, but by means of external marks.

What you have discovered is a recipe not for memory, but for reminder. And it is no true wisdom that you offer your disciples, but only the semblance of wisdom, for by telling them of many things without teaching them you will make them seem to know much while for the most part they know nothing. And as men filled not with wisdom but with the conceit of wisdom they will be a burden to their fellows.vii

Two Simple Directions

But then again, how can intelligent prostheses such as the memex, or Plato’s take on writing as a prosthetic device, be of any interest for architecture? There are two main directions in which prosthetic intelligence can unfold to become critically important to consider for architects in their practices today. The first one is a spatial notion that Bridle touches upon in New Dark Age which he calls code/spaces. This argument is perhaps more infrastructural than disciplinary and is also part of Koolhaas’s recent research topic, the rural and its systems.viii The second direction is one that asks whether a paradigmatic shift is currently channeled by the imagery generated using prosthetic devices such as software driven by AI. I am more invested in the second argument because of the fundamental qualitative and disciplinary questions it raises. This so-called AI-imagery is hard to define as simply image or photography and requires close consideration to uncover its essential distinctive qualities.

1: Code Space

For Bridle, code/space defines an ever-growing typology of buildings best exemplified by airports. They are spaces whose primary functions rely on prosthetic intelligence. These spaces are not what they are without their prosthetic counterpart. For example, in the case of airports, it is a computerized network that makes them function. In Bridle’s words:

If, when they [passengers] find themselves at the airport, the system becomes unavailable, it is not a mere inconvenience. Modern security procedures have removed the possibility of paper identification or processing: software is the only arbiter of the process. Nothing can be done, nobody can move. As a result, a software crash revokes the building’s status as an airport, transforming it into a huge shed filled with angry people. This is how largely invisible computation coproduces our environment.ix

This total dependence on computerized systems is a fairly recent reality. Before the global outreach of the Internet any space could function independently, but it is now unthinkable for many spaces to even be usable without a connection to the global network.

For example, in a simpler fashion, office spaces are now totally dependent on internet access. It is hard to imagine any office that would function more than ten minutes without it. Architecture’s relationship to prosthetic intelligence hence must be thought of, but this area is very often left under designed because of its seemingly invisible nature.

On the other hand, the RAM house (fig. 4), a 2015 project by the Italian group Space Caviar responds ironically and yet very materialistically to the invisible reign of electromagnetic waves. The project proposes to incorporate an operable Faraday Cage into a house. A Faraday Cage is a simple metallic structure that, if it wrapping an entire space, nullifies the electromagnetic wave presence in it. Space Caviar makes use of materials that are normally only used in technical environments like radar absorbent material. The RAM house is hence extremely paradoxical: its raison d’être is to cut off its inhabitants from all prosthetics. It is anti-cyborg, anti-network, anti-prosthetic if you will. And yet, by being so, it is the most hybrid a house gets in its built form in relation to digitization.

These two typologically different examples illustrate how at the level of spatial organization, architecture embraces a simplistic, distanced, diagrammatic relation to technology while remaining totally dependent on it.

Figure 4 RAM House, Space Caviar, courtesy of Space Caviar

2: Simplicity = Aesthetics

I recently curated an exhibition called “Aesthetics of Prosthetics” at the Pratt Institute’s Siegel Gallery with my colleagues Ceren Arslan, Can Imamoglu, and Irmak Ciftci, where we tried to keep a track-record of what we understand today by “human-machine hybrids” in design processes. In our call for projects, we defined prosthetic intelligence as any tool or device that enhances your mental environment rather than the physical . Here is a familiar example: when at a restaurant with friends, you reach out to your smartphone to do an online search for a reference to further the conversation. you are using prosthetic intelligence.

Today, far from Haraway’s “stylistic and rhetorical bravado” on cyborgs as an idea,x we have finally, literally become cyborgs. Following McLuhan’s dictum understanding pencils as extensions of our brains,xi a computer or smartphone are similar extensions and are forms of prosthetic intelligence. And this is just the beginning. Soon, these prostheses will disappear from sight and be hidden somewhere behind our ears or under our skin. But what does that have to do with architecture?

Just like engineers who designed machines that opened the path to a new aesthetic paradigm, intelligent prostheses are unveiling yet unseen images. Le Corbusier wrote about “eyes that do not see” to express the lack of attention that was given to the exceptional aesthetics of machines in the early twentieth century. Similarly, convolutional neural networks, a machine learning process, coupled with designers’ guidance, produce imagery today that is unprecedented and uncanny.

In that field, architect Karel Klein’s recent studio work at Pratt, University of Pennsylvania and Sci-Arc is probably the best example. Students in her studios are training artificial intelligence to work with architectural material. Thus, intelligent prostheses learn to read and combine architectural imagery (plans, elevations, sections, photos…) in a familiar and yet extremely strange way (fig. 5). The result obviously holds photographic evidence of its originator (images of specific buildings) but becomes something else. Speaking during the “Aesthetics of Prosthetics” symposium organized within the framework of the above-mentioned exhibition, Klein said:

I don’t know how to position the things that I’m doing with students in terms of representation. We primarily work with images. We work beyond those but that’s where we begin. That’s where the beauty is, and that’s where everything is, it’s in the images. But the images are not representational. They are not representations in my understanding of them. They are originals. Part of what’s strange about them is that at their best, they resemble photographs. That is the strange part too, because photographs are of course not originals. You gaze upon them and they are familiar in that they are almost convincingly already out in the world. And so they are not representation, in the way that we understand representation traditionally in architectural discourse.

Figure 5: Amir Ashtiani, Uncanny Aesthetics, model, courtesy of Amir Ashtiani

In the context of the panel, Klein’s answer was informed by the question about whether this AI imagery is simply representational or is out-in-the-world. In that regard, we find ourselves faced again with what seems to be the contemporary divide in architectural academia in the East Coast: to represent or not to represent. Luckily enough, the biggest aficionado of the representation polemic was among the panelists. Mark Foster Gage, in a heated answer to panelist Neyran Turan’s labeling of photorealistic pursuits as naïve, again put forth the idea that there exist two firmly established camps in today’s architectural discourse. In his words:

I think that architecture is in danger of being rested away by those interested in representation. And the characteristics of those representations are almost always simple geometries, pastel colors, easy to understand forms and a little bit of humor. You see it in MOS’s or Neyran’s work. And I think there’s a project of representation there that quite honestly is dangerous to architecture because it is re-instantiating architecture in the discourses of art. In your presentation you talked about art [to Neyran], and in his article on indifference, Michael Meredith talks about art. It is all about relating architecture to the history of art as a representation. And in your talk you use the term naïve photo realism, which I think is hilarious, if not totally offensive in that there is a group of architects today very interested in questioning the nature of how people perceive and understand the real, which they are doing through photo realism, which is incredibly difficult. And that is something that Karel’s students are playing with in an exquisite and gorgeous way. The tools and prosthetics of architecture today are being best deployed in allowing people to question the very nature of what is considered reality.

Indeed, images generated by intelligent prosthesis raise a fundamental question about the reproduction of reality, similar to the questions raised by the invention of photography in the first half of the twentieth century.

In Walter Benjamin’s 1931 piece A Short History of Photography, Benjamin quotes from Bertolt Brecht writing about photo-realism’s inability at truly bringing reality to the viewer. Brecht’s words resonate strongly in today’s image saturated world:

Less than at any time does a simple reproduction of reality tell us anything about reality. A photograph of the Krupp works or GEC yields almost nothing about these institutions. Reality proper has slipped into the functional. The reification of human relationships, the factory, let’s say, no longer reveals these relationships. Therefore something has actually to be constructed, something artificial, something set up.xii

Benjamin argues along the same lines as Brecht and proposes to distinguish between creative and constructive photography. For Benjamin, creative photography is described by its relation to what is fashionable and characterized by its motto the world is beautiful. He then defines constructive photography as creative photography’s counterpart: “Since, however, the true face of this photographic creativity is the advertisement or the association, its legitimate counterpart is exposure or construction.” xii

Can the work pursued around AI images be understood as constructive and exposed in Benjamin’s sense? For Benjamin, the first to succeed in photographic constructivism were surrealists. Today, AI generated images are being called deep-dreams or computers’ dreams. Like surrealists who have been revealing the uncanny beneath the familiar in daily life, the AI generated architectural images from Klein’s studios estrange familiar architectural elements such as walls, porticos, windows, or arches into a stream of repeated and distorted elements where the original elements can be recognized and yet the resulting composition is novel. These images are not photographs; At their best, they resemble photographs. At the same time, they look very real. This very doubt about the nature of the work is what renders it fertile. In other words, in this process, the underlying mechanism of the prosthetic device is exposed and selectively exacerbated by the author. The surrealist artist Man Ray worked in a similar way with photography, refining and personalizing the production of photograms (photographic prints made by laying objects onto photographic paper and exposing it to light) to such an extent that photograms have been called rayographs since then. In that regard, we can say that both Man Ray’s rayographs and Karel Klein’s use of Adversarial Neural Network for constructing imagery are exposing (their own method of production) and constructive (as they are using existing “building bricks of reality”.)

The art world had its share of AI generated painting discussion in late 2018. The very polemical and pricy auction of a rather mediocre portrait produced with the help of Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) infuriated artists proficient in using AI in their work. The project of the art collaborative Obvious who produced the painting was a marketing product (the artists admit it) making extensive usage of an algorithm developed by the young artist Robbie Barrat.xv

To conclude, an aesthetic and hence simplexvi relation with technology opens the door to what seems to be uncharted territory. As AI paintings are gaining their places in large private collections, we ask ourselves whether prosthetic intelligence is not a smokescreen, feeding the unending hunger for novelty-for-novelty’s-sake of a commodified art market. For both art and architecture, intelligent prostheses still have everything to prove to gain disciplinary legitimacy. And yet, a piece of theory-to-come around these tools and the questioning of their outcome will be critically relevant to provide the foundation for a constructive—and not simply associative or advertising—body of work in the third decade of the twenty-first century.

Alican Taylan is an architectural designer and engineer. He holds a Master of Engineering from the National Institute of Applied Sciences, Lyon and a Master of Architecture from the Pratt Institute, New York. Prior to working in architecture, he has worked as a naval designer. He has later worked in the offices of Peter Eisenman, Shigeru Ban, and Thomas Leeser, where he currently practices.

He co-teaches with Thomas Leeser an advanced graduate design studio at Pratt Institute. He recently curated an exhibition, Aesthetics of Prosthetics at Pratt Institute’s Siegel Gallery, and published a project in Log 47.

iAlejandro Zaera Polo, Well Into the 21st Century (El Croquis N.187, 2016).

ii The term, originated in the late 1970’s in the wave of post-isms with the goal of distancing social sciences from anthropocentric considerations, is now broadly used in environmental sciences, architecture and philosophy.

iii Slavoj Žižek, Like a Thief in Broad Daylight (Seven Stories Press, 2018), 46.

ivIbid

vOne can type in “brain computer interface on mouse” on a search engine to find dozens of examples of disconcerting experiments run on mice.

viJames Bridle, New Dark Age, (Verso, 2018), 23.

viiPlato, Phaedrus, trans. Nehamas, Alexander, and Paul Woodruff (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1995), Vol. 274b-277a.

viiiRem Koolhaas, Countryside Manifesto (https://oma.eu/lectures/countryside, 2012)

ixJames Bridle, New Dark Age (Verso, 2018).

xCary Wolfe, Introduction to Manifestly Haraway (University of Minnesota Press, 2016), vii

xiMarshall McLuhan, and Quentin Fiore, The Medium Is the Massage (Toronto: Random House, 1967).

xii Benjamin, W. “A Short History of Photography.” Screen 13, no. 1 (January 1972): 5–26.

xiiiIbid

xiv Gabe Cohn, AI Art at Christie’s Sells for $432,500 (The New York Times, 10.25.2018).

xv James Vincent, How Three French Students Used Borrowed Code to Put the First AI Portrait in Christie’s (The Verge, 10.23.2018).

xvi For a complete definition of aesthetics, refer to Jacques Ranciere’s work on the aesthetics-politics relationship or speculative realists’ definition of the term as the fundamentally surface qualities things express to one another.