The Responsibility of Design

The Responsibility of Design: Can Socio-Political Disagreement Be Mediated Through Design?

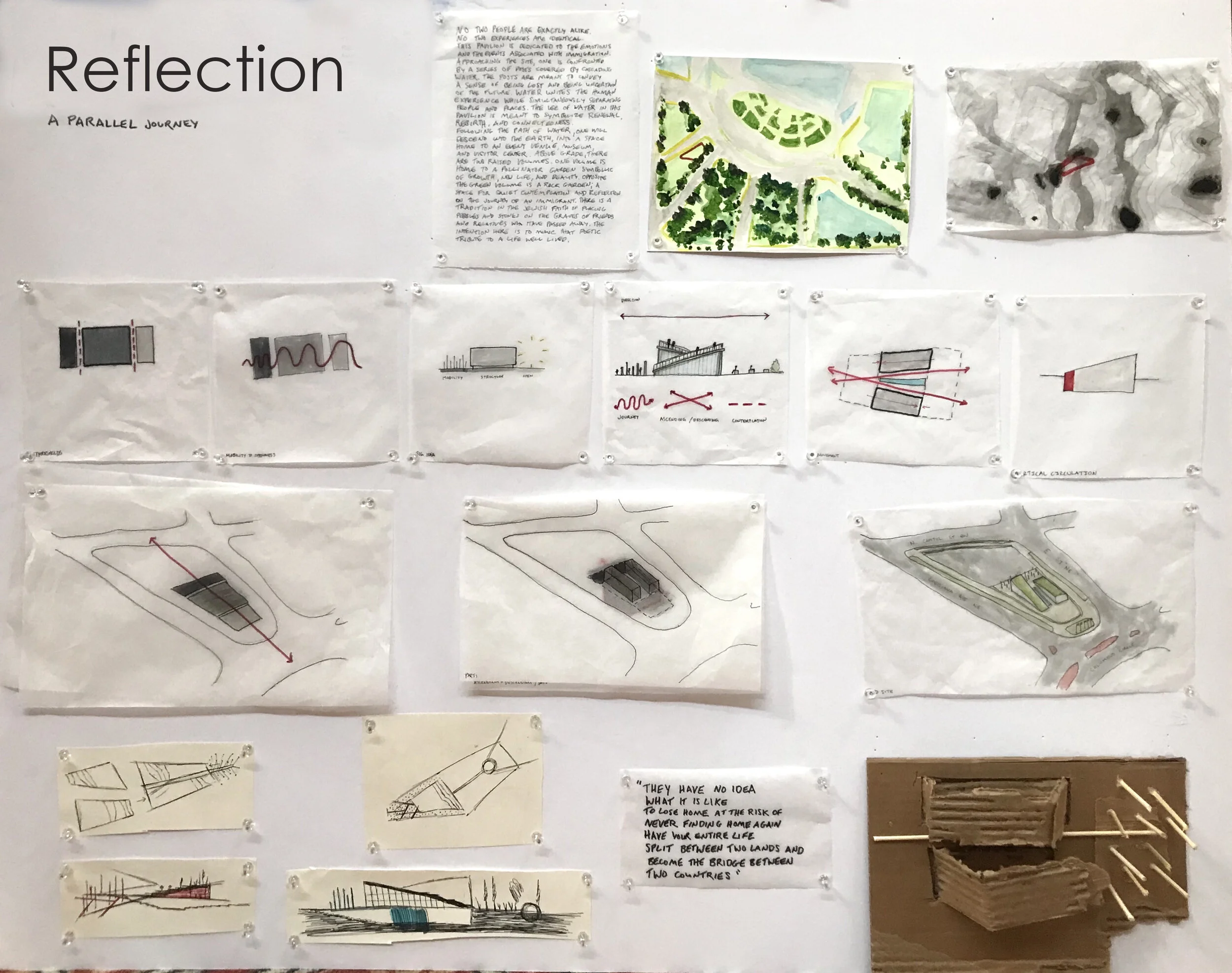

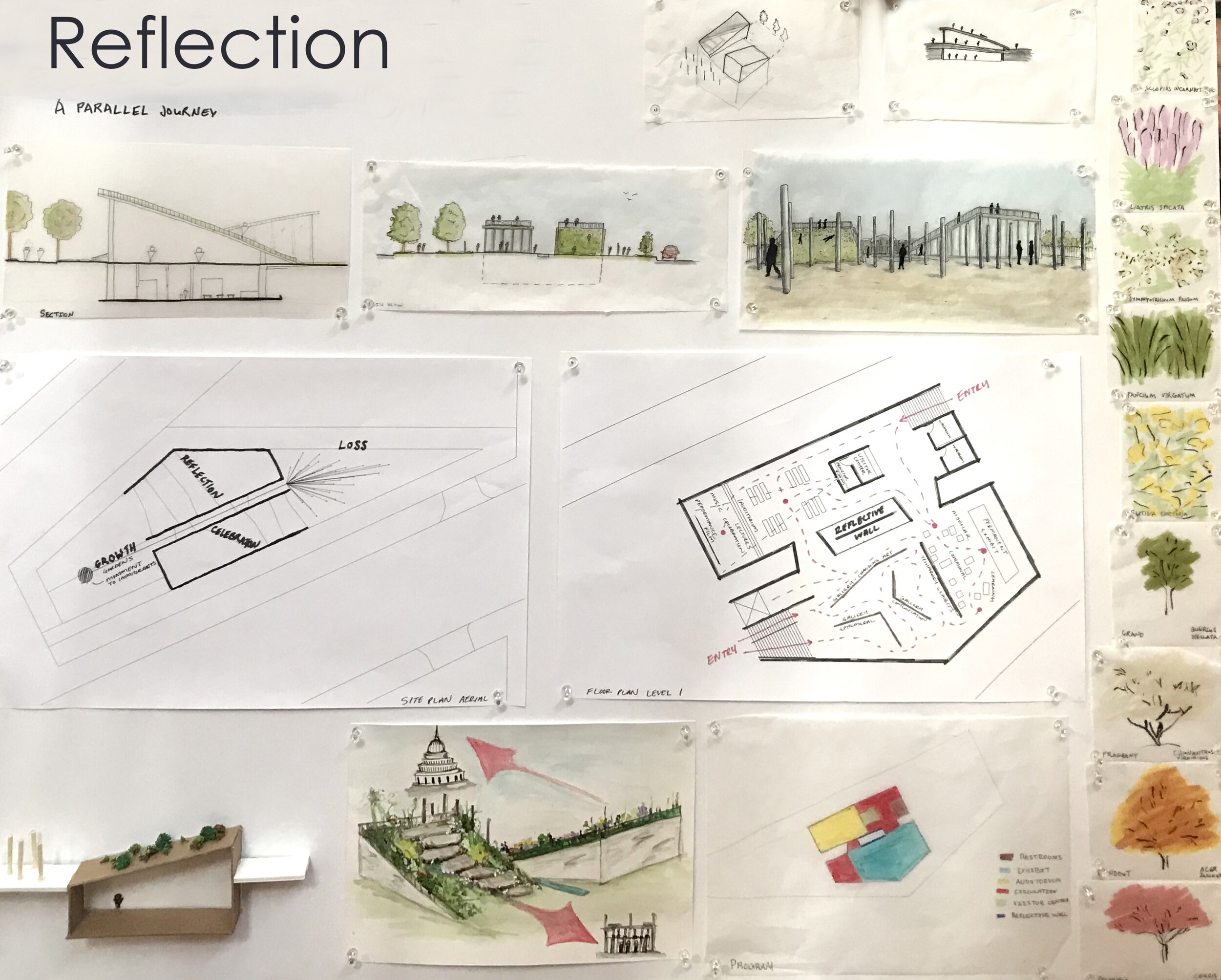

The Reflection Pavilions, a proposal for Immigration Memorial competition. Photograph provided by Chalya Aaliyah Nimyel (Howard University, M.Arch’22).

Designed by Saud Alsebeiei (University of the District of Columbia, BS.Arch’20), Jefferson Choi (University of Maryland, M.Arch’21), Valencia McDowell (Morgan State University, BS.AED’20), Chalya Aaliyah Nimyel, Eliezer Perez (Virginia Tech Washington, M.Arch’21), Abigail Sekely (The Catholic University of America, BS.Arch’20)

In an era of post-truth conversations, the delicately nuanced state of socio-political debate has increasingly become an incomprehensible din of angry voices, frustrations, and culture war campaigns waged across all media. The fractured political timbre of the United States urgently calls for civil discourse and real solutions to the existential issues of our time, be them social, environmental, economic, moral, or generational. Within the welter of issues being discussed, it has become difficult to separate and appropriately choose which issue is worth the public’s attention beyond the customary soundbite, swipe, or mouse click. The question of finding possible solutions to the prevailing existential issues of the age may very well be found in design, and particularly in design pedagogy. Educators have a unique platform in design programs to not only tap into the issues that people care about, but to also approach them with normative and descriptive rigor. What is the role of the designer in such public conversations, and do designers need to take a more proactive role in seeking solutions to these complex questions? The answer is an increasingly resounding yes. Designers have a moral obligation and mandate to address the pressing issues of our time, as well as to pursue a committed and inculcated practice.

The bitter political divide has entrenched all corners of the spectrum deep into their positions and their perceived truths, rather than seeking actual solutions to the challenges they face. It has become easier to oppose something or someone than to work towards resolving the impasse. Students at design schools are trained to address challenges by seeking appropriate lines of questioning and rigorously testing them, instead of attempting to find a solution at once. It is the hallmark of design thinking: The systematic pursuit of empathetic questioning could lead to possible solutions, which perhaps have never been considered. If design-thinking’s successful model is predicated on how one approaches a challenge, then the potential solutions to many societal maladies are ones based on design approaches. In short, explore asking questions first, live the questions, and then arrive at the potential solutions through discourse.

With regards to some of the more strident socio-political issues, discursive design may offer options that have not previously been considered. In essence, discursive design is ideas-driven, with an end goal of creating discourse and expanding the conversation.ᶦ Whether critical, reactive, celebratory, or contemplative in nature, the discourse stems from that initial catalyst of a discursive, conversational idea. Design predicated on a discursive idea cannot be easily dismissed and it elicits a response of some kind, be it intellectual or emotional. While most architecture is primarily driven by function and program pertaining to the clients’ and constituents’ needs and desires, there are practitioners who feel that architects could and should do more. It is at this point where discursive design has the potential to enter public conversation, and architecture has the opportunity to gain a rich, intellectual, and emotionally textured meaning.

The realm of public spaces presents exciting opportunities for such discourse to take place. When a design in a public space begins to elicit responses in people, these responses lead to conversations, and perhaps, through a dialogue that is moderated by the designed space, solutions may develop and quietly materialize into people’s lives . Responses to architecture can be intellectual, emotional, reflexive, or even unconscious. Sometimes they are instantaneous, and at other moments require a certain level of introspection and quiet reflection. What is most important is that the design be discursive: that the initial design idea drives and expands the conversation in a Socratic way. When architecture achieves a type of intellectual and civil discourse, it frees itself from being an immovable feast, compelling people to engage in dynamic conversations that have motion. Students in design programs today understand and are drawn to this notion, and it is why they respond to a program with enthusiasm when a discursive idea is the driver.

With discursive design having the potential to address the critical social issues affecting the world today, one must ask if architects have an inherent responsibility to partake in the conversation. If environmentalism has taught the architectural community that there are moral obligations to the Earth which require a focus on sustainability, then the same moral imperative could also be applied to placing focus on social responsibility. This imperative may reveal itself in equitable housing or ecologically driven projects responding to natural disasters. While these projects are worthy and manifestly important areas of focus, design must also commit to engaging beyond these parameters. Division on social issues can be just as corrosive as global warming, and it is more readily identifiable in most cases, as social reactions tend to move more swiftly than climate change. It is for this reason that architects and landscape architects, particularly those who have the opportunity to work in the realm of public space, must take a leading role in using spaces to create and proactively participate in that discourse. While many architects see the potential impact that their work can have in shaping the built environment, the architectural community tends to be silent when opportunities to take a position on social issues present themselves. It is time to engage the broader community more concertedly, and actively pursue the means to engage in the conversations surrounding social issues. Two case studies on immigration and race demonstrate how projects can begin to imbue the collective social consciousness, and how event-based subjects that capture the public’s attention can create opportunities to revisit conversations that need further investigation.

Case Study 1: Undoing the Mythology of Confederate Monuments

As of February 1, 2019, more than 150 years after the American Civil War, the Southern Poverty Law Center has identified 1,747 Confederate place names and other symbols in public spaces. The majority of these monuments are located in Southern states, but there are several in bordering and northern states as well. In total, 31 of the 50 states and the District of Columbia have a Confederate monument of one form or another. In North Carolina alone, 35 monuments have been added since the year 2000, dispelling the myth that all of these monuments somehow fall into the category of requiring historic preservation. As of early 2019, there were over 100 public schools, 80 counties and cities, and 10 major U.S. Military bases named in honor of Confederate military leaders and icons. Additionally, five Southern states observe official paid holidays that honor the Confederacy or its soldiers and leaders.ᶦᶦ

The continuing existence of Confederate monuments, and the ensuing debates on institutional prejudice, unconscious bias, and revisionist history, demonstrate that the United States still has a long journey ahead in its evolution to be a truly equal, inclusive, and just society. The monuments themselves have created an illusory, false mythology of heroism, and have obscured the actual history of the racism they represent. Furthermore, the current state of politics in the United States has exacerbated the divisive rhetoric. In the wake of the events that took place in Charlottesville, Virginia on August 12, 2017 and the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, deliberate and substantive conversations on race, history, and appropriate approaches for addressing the future of these monuments have taken place at the national level. The legitimacy and future of Confederate monuments need to become part of the critical and urgent conversations on race that are held in public if the United States is to have any hope of fulfilling its ambition of being a true model of freedom and equality. It should not be permissible to memorialize the prejudice that these monuments represent in public spaces. Instead, a designation of appropriate venues, or designed and contextual adjustments, could speak truth to the myths surrounding these markers of history.

It was Frederick Douglass’ such wish to contextualize and make a monument more appropriate, when he wrote a letter to the editor of the National Republican newspaper about the Charlotte Scott Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C. on April 19, 1876. The statue was the first in the country erected to Abraham Lincoln and funded solely by freed slaves, including the eponymous Scott who used the first five dollars of her earnings as a free woman to begin the funding for the monument. The design of the statue however, had no input from the freed slaves who funded it; and it is precisely in the depiction of the two figures in the statue where Douglass took issue:

Admirable as is the monument by Mr. Ball in Lincoln Park, it does not, as it seems to me, tell the whole truth, and perhaps no one monument could be made to tell the whole truth of any subject which it might be designed to illustrate… The [freed slave] here, though rising, is still on his knees and nude. What I want to see before I die is a monument representing [him], not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man. There is room in Lincoln Park for another monument, and I throw out this suggestion to the end that it may be taken up and acted upon. ᶦᶦᶦ

One hundred and forty years later, Douglass’ suggestion remains unanswered, and the debate continues. There is currently a motion underway in the District of Columbia to have the monument removed or amended. Critical in this motion would be a voice from the design community. A rich opportunity for discursive design, where additional context should and must be incorporated, exists here.

Thomas Ball, Emancipation Memorial, 1876.

Photo by yeowatzup / CC BY 2.0

Another case in point is the sculpture Rumors of War by the artist Kehinde Wiley, unveiled in early December 2019 at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, Virginia. The large sculpture depicts a contemporary African American youth heroically mounted on horseback looking back over his shoulder. The artwork stands in counterpoint to its source material: a rendition of the statue of Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart from 1907, as well as the other Confederate statues that line the city’s famed Monument Avenue. As Wiley puts it, “In these toxic times art can help us transform and give us a sense of purpose. . . We come from a beautiful, fractured situation. Let’s take these fractured pieces and put them back together.”ᶦᵛ

If the gesture of the sculpture as a form of response to an offensive monument seems easy and logical, it is because it is so. The installation is an example of the conversation that public art has often addressed―that of reaction versus veneration. Art can fall into one of these two camps, and sometimes both. Architects and landscape architects can and should also participate in the conversation about the broader design gesture and design public spaces that can straddle these opposing themes.

Kehinde Wiley, Rumors of War, 2019.

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Virginia Sargeant Reynolds in memory of her husband, Richard S. Reynolds, Jr., by exchange, Arthur & Margaret Glasgow Endowment, Pamela K. & William A. Royall, Jr., Tom & Angel Papa, and additional private donors

Photo: Travis Fullerton © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

An important avenue in cementing such reactionary approaches to perceived history and existing context in public spaces lies in pedagogy. In the course “Contemporary Issues in Architecture,” taught during the Fall semesters of 2017 and 2018 at Howard University’s College of Engineering & Architecture, students were asked to read and write a short response to Kevin Lynch’s seminal text The Image of the City, written in 1960. Lynch’s writing focuses on the legibility of urban spaces and how individuals map the shape of cities as they navigate through them. Specifically, he defines the physical city by dividing it into a series of recognizable elements: paths (streets and sidewalks), edges (large physical boundaries such as rivers and built spaces), districts (neighborhoods), nodes (significant points where paths may converge), and landmarks (monuments or symbols). Among the landmarks, monuments and symbols each have defining characteristics, as well as ambiguity in terms of one concept overlapping or sharing qualities with its respective adjacency.ᵛ

The question of what defines a city was placed before the students to discuss. They were then asked to describe the following cities using descriptive terms that help define and differentiate them from the others―Washington, D.C., New York, Miami, Chicago, New Orleans, Houston, and Los Angeles—with the only rule being that the descriptive terms had to be physical characteristics. Most responses drew on landmarks that emblematically defined the city. While not everyone had been to the selected cities, there were common associations driven by proliferated images in books, television, movies, and online media.

Defining these elements as Lynch does is a useful way for designers to study the morphology of existing cities. Lynch’s ideas provide a baseline to study how cities can be developed and redesigned, or how new cities can be designed altogether. While the social component of cities was not the intention of Lynch’s essay, students’ general response to the essay was that it arguably should have been—cities are equally defined by associations of events or the movements of people, and by what the residents do there. In other words, a city unpopulated by people is merely an abandoned collection of organized forms. Architecture cannot be disassociated from its inhabitants. If people give cities a sense of place, the physical characteristics become part of a reputational or associational capital. While architecture and the idea of place are nearly inseparable, associations to a place via people and events are sometimes more dominant. Whether appropriate or unfair, these associations exist and create an ethos that cannot be overlooked.

The cities previously mentioned were then revisited, applying attributes to paint a more thorough picture of their “place.” Washington, D.C., for example, became the emblematic posterchild for political rancor and powerplay. Yet it also garnered a wide and divergent array of descriptions such as transient, young, international, cultural, gentrified, sleepy, and even beige, as one student put it. New York, on the other hand, became a city of constant motion, attitude, and edge―a “center of the universe” ethos was ascribed. These attributes, as descriptors, revealed a new layer of urban definition for each city.

When the students were asked what the associations were of Charlottesville, the nearly unanimous response heaped the unwanted moniker of racist upon the city’s shoulders. The questions were then posed: If this association were a design opportunity, what would help to mollify this association? How could a designer transform the stigma of an event to a symbol of healing, or at the minimum, discourse? The physical city could become a canvas to act upon, beginning at the nodes where the events occur, just as it was for Kehinde Wiley in Richmond.

The final question was two-fold: What should be done with Confederate Monuments, and if removed, what should replace them? The numerous proposals varied, from ones that took destructive and confrontational approaches to the monuments, to others that opted for a more Wiley-esque approach that used the context to create dialogue. For every proposal to remove a monument and replace it with another, there was the proposal to leave the monument in place but somehow alter it with added context. These alterations ranged from minimal interventions of adding informational plaques, to redesigning the public spaces entirely to transform the monuments into an experiential form of discourse. No response was wrong, each merely different in its goals.

One such project, The Keystone Monument, a proposal by students Christian Hudson (M.Arch’21) and Ayman Lawal (M.Arch’21), called for the removal of the statue of the Confederate general John B. Gordon in Atlanta, Georgia. Gordon was not only a general, but a subsequent Georgia State Senator and known leader of the Ku Klux Klan. The unredeemable statue, erected in 1907, stands on the State Capitol grounds, and expresses unmistakable support for the systemic racism that Gordon and his statue symbolize. There should be no question as to why it should be removed. In its place, Hudson and Lawal proposed a monument composed of a series of broken arches representing the path toward racial justice at different stages in American history. With each successive growing (and at times shrinking) arch, visitors to the monument would experience the progress or regression in the path toward racial equality at a given moment. At the center, the most complete arch, missing its keystone, calls for each person who approaches it to be the keystone itself, thereby representing a unified whole. The Keystone Arch, blocked on all sides, ushers visitors to retrace their steps and guides them onto the adjacent pathways lined with benches, which offer additional history and context. The purpose of the monument is not just one of reflection and the telling of history, but of a very humanistic engagement within the space in front of the State Capitol, whose own difficult history needs to be recognized in a way that dignifies the long and circuitous walk to equality.

While identifying public spaces in need of adjustment is a helpful exercise, it is not as straightforward as simply pointing out the associated facts and identifying monuments that need to be addressed. Reputational or associational capital should be grounded in the physicality of places that directly address issues, where people can share the cognitive burdens of racism, and in so doing take steps to move forward. A complaint frequently voiced by architects is that political forces do not do enough to include designers when the conversations touch upon the shaping of spaces. The response might be that architects are not forceful enough in having their voices heard due to client or constituent demands, funding, or the challenges of battling code. While the client or the code are real constraints, they should not be used to concede a position. Ideas can take hold outside of the academic discourse by giving students the agency to carry on the conversation into practice.

Case Study 2: The National Immigration Memorial

Every year, students from six architecture programs based in the greater Washington, D.C. and Baltimore areas gather at the National Building Museum to compete in mixed teams for a one-day design charrette.ᵛᶦ The program for 2019’s competition, proposed by Howard University, was to design a National Memorial dedicated to immigration located between Washington, D.C.’s Union Station and the U.S. Capitol. The location of the proposed project was intentionally critical; by being positioned between Union Station and the U.S. Capitol, the project would speak to the movement of people on the one side, and to the ongoing and contentious debate surrounding immigration on the other.

The impetus for the project was born out of the language of the official Mission Statement of United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, which changed on March 6, 2018 to eliminate a passage that describes the U.S. as “a nation of immigrants.”ᵛᶦᶦ The change was made with little publicity but speaks volumes to the volatile state of immigration today and warrants a discursive design response. The most challenging question that the students faced in the competition was how architecture, and specifically a memorial, can transmit the notion of immigration and multiculturalism, relate the multitude of different narratives, and help begin constructive conversations on the immigrants’ experiences.

The teams embraced the challenge, with each student member having a personal story to tell. Just as with the Confederate Monuments project, the design proposals varied. Some told the immigration story as a chronology, while others told the story thematically and focused on specific areas―from stories of those pursuing the “American dream,” to those seeking asylum and fleeing persecution, to those whose immigration was forced as a result of slavery or war. Some designs created literal references to walls, while others were metaphorical, with fusions of ecology and space-shaping leading the narrative. Whether a story of celebration or a story of tragedy, or both, every design was driven primarily by a discursive engagement with the public.

The Reflection Pavilions, completed by a team comprised of students from every participating school began with the notion that immigration is an event that is fraught with emotional and physical sensations, and no two people or experiences can be exactly alike. Approaching the site, one is confronted by a series of posts covered by cascading water meant to convey a sense of being lost and being uncertain of the future. Water unites the human experience while simultaneously separating people and places, and symbolizes renewal, rebirth, and unity. Following the path of water, a visitor will descend into the earth, into a museum and a visitor center. Above grade, there are two raised volumes. One volume is home to a pollinator garden symbolic of growth, new life, and beauty. Opposite the green volume is a rock garden―a space for quiet contemplation and reflection on the journey of an immigrant. There is a tradition in the Jewish faith of placing pebbles and stones on the graves of friends and relatives who have passed away. The intention is to mimic this poetic tribute to a life well lived.ᵛᶦᶦᶦ

In discursive design, one technique is to set the designer and the spectator as interlocutors so that the design itself poses questions. The Immigration Memorial competition took on a highly charged subject, and allowed the design teams, the jury, and the public to draw their own conclusions. Those who attended the subsequent competition exhibition responded enthusiastically to each team’s design proposal.

A Compass of Social Suggestion

If the denouement of an architectural education is to instill passion for any project, then professors need to meet students where they are most comfortable feeling passionate. Many students today are increasingly passionate about issues in the public domain—social issues, ideas that impact the way people live, the environment—everything from political timbre to topics of economic strata. They are moreover most engaged about these ideas on their own media platforms. As such, the conversation needs to expand beyond the limits of analog and digital exploration as form-making, and incorporate the all-encompassing content, including the messaging, of what is being designed.

To inspire a student today in architecture means to create projects that form part of the public, social diaspora, and discourse. Students are excited about the possibilities of creating something that could bring forth real change in areas of their interest, and to have the choice in designing how the change may manifest itself. As they begin to learn the rigors of architecture, their enthusiasm needs to be maintained through subject matters that hold their attention. Design students should be made to feel as though what they have designed really matters and to have the meaning of what has been created inhere within.

Architects and planners often operate under labels of “form-makers,” or “problem-solvers”. While the former label addresses an obvious duty, the latter is a dangerous assumption. Make no mistake: architects and designers are not a panacea to societal ills—the lessons of Modernism are proof of this, and history is rife with the mistakes that designers have made, however well-intentioned. Utopian ideals often fail, at times quite tragically or irresponsibly. What architects and educators can do, however, is to lead with responsible actions and a sense of duty, inviting people into conversations about responsibility. How can design thinking and discursive design affect social thoughts? Perhaps we begin by being deliberate in our attempt to make people responsibly think about ideas, and then as an intended consequence, allow the imagination to provide a contemplative path towards solutions.

Martín Andrés Paddack is an Assistant Professor of Architecture at Howard University. With previous teaching experience in Fine Arts and English, Martín is most interested in finding deeper meanings in architecture through the intersections of color, art, cultural identity, social responsibility, and sustainability. Martín began his career as an artist before turning to architecture, and has exhibited paintings at galleries and museums around the world. He studied Fine Arts and English at the Hartford Art School/University of Hartford and earned master’s degrees in Architecture and Sustainable Design from The Catholic University School of Architecture & Planning.

i See Bruce Tharp and Stephanie Tharp, “What is Discursive Design,” Core 77, December 9, 2015, www.core77.com/posts/41991/What-is-Discursive-Design.

ii See Southern Poverty Law Center, “SPLC report: More than 1,700 monuments, place names and other symbols honoring the Confederacy remain in public spaces,” Features and Stories, June 4, 2018, www.splcenter.org/news/2018/06/04/splc-report-more-1700-monuments-place-names-and-other-symbols-honoring-confederacy-remain.

iii Frederick Douglass, “A Suggestion,” National Republican, Washington, D.C., April 19, 1876. From Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/sn86053573/1876-04-19/ed-1/, accessed August 6, 2020.

iv Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, “Sculpture Created by Kehinde Wiley for VMFA,” About VMFA, www.vmfa.museum/about/rumors-of-war/.

v Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1960), 46-90.

vi The Interschool Student Design Competition held annually at the National Building Museum is comprised of the following universities: Howard University, The University of Maryland, The Catholic University of America, Virginia Tech University WAAC Campus, Morgan State University, and the University of the District of Columbia.

vii United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Mission Statement,” About Us, March 6, 2018, www.uscis.gov/aboutus.

viii Project description and images provided by Chalya Nimyel (Howard University, M.Arch’22). Project teammates: Saud Alsebeiei (University of the District of Columbia, BS.Arch’20), Jefferson Choi (University of Maryland, M.Arch’21), Valencia McDowell (Morgan State University, BS.AED’20), Eliezer Perez (Virginia Tech Washington Alexandria Campus, M.Arch’21), Abigail Sekely (The Catholic University of America, BS.Arch’20).